When I walked off the college stage in 1987, steeped in English literature, the first thing I did was to get into my car, drive across the country to Los Angeles with $500, a U-Haul full of music gear, and the dream of being the next Billy Joel.

That didn’t turn out so well.

What worked out slightly better was writing. My first actual job in Los Angeles was writing and editing marketing research reports for local car dealerships. While I did that, I also immersed myself in writing plays and screenplays. I read as many books as I could on the craft. I took classes. I read hundreds, thousands of scripts. And I wrote. I wrote and wrote and wrote.

That didn’t turn out so well, either.

But what I learned was how to recognize the unique patterns, structure, and language of script writing compared to other forms of writing. Scripts are unique in the writing world because they generally are not the final art form (though for many of them, I certainly beg to differ).

Scripts are unique #writing b/c they’re not the final art form, says @Robert_Rose via @cmicontent. #CMWorld Click To TweetScripts are inherently created to be interpreted through other mediums like stage, film, or the web. In many ways, scripts are the “instructions” for how to tell the story, capturing the movement, speech, and even technical directions.

The tension between screenwriters and directors and the interpretation of scripts is legendary in Hollywood. The famous director Robert Altman said, “I don’t think screenplay writing is the same as writing. I mean, I think it’s blueprinting.”

Writing scripts has benefits

Today, in addition to my role as book author, consultant, and advisor, I’m a podcaster, webinar presenter, speaker, teacher, and occasional (and reluctant) video host. I write a lot of scripts for myself and others.

Writing a script for your podcast, webinar, video, or presentation has a number of benefits:

- You stay true to time. With a script, you can practice and rehearse to know exactly how much time the presentation requires. With a script, I can stay generally within 3% of the allotted time. This means I am one or two minutes early or late for every 30 minutes of a presentation. (If you want to make any event organizer unreasonably happy, being on time is the No. 1 way to do that.)

- You know you’ll hit on the core points. Remember that third point you spent two hours fine-tuning? Or do you recall when you didn’t write the point into your script because your slide would remind you? You forgot it, didn’t you? A script helps you make sure that you deliver all of your points concisely and never forget to include them.

- Writing it helps polish your material. If you write it word for word, you’ll simply know it better, and your performance will be better as a result.

The challenge of writing scripts

When I ask people why they wouldn’t script their presentations, videos, etc., a common response is that they are uncomfortable with the format. They are afraid that if they write out their speech, it will sound stale and unnatural.

But there are some fun secrets to creating scripts that are useful tools, just like blueprints are for an architect. Before I go there, let’s explore some of the “rules” I often see about writing scripts for video and audio and why I’m not such a fan of them:

- Use shorter words instead of longer ones.

- Use contractions instead of full words (e.g., “can’t” instead of “cannot,” and “don’t” instead of “do not”).

- Use teleprompters or memorize your scripts always.

- Get rid of tongue twisters.

- Never repeat yourself. Never. Never. Never.

As I said, I disagree with these five rules. If you prefer longer words and they fit into your speech patterns, this rule is adjustable. If you are a more formal speaker, then the usage of “cannot,” “do not,” “could not” instead of “can’t,” “don’t” or “couldn’t” can help you make a more emphatic point. Do. Not. Worry about this rule.

Mandating teleprompters or memorization also should not be a rule. As you’ll see further below, scripts can be used in ways that go beyond teleprompters or memorization. And if you want to wax poetically and speak to something where mystic moonlight moments meet softly, and somewhere songbirds tweet, well then, you absolutely should.

And of course, of course, of course, you can repeat yourself. It’s your lyric to sing.

With these rules out of the way, let’s look at the three secrets I’ve found to create better scripts.

Secret 1: There are no extra points for style

Writing for speaking versus writing for reading is different. Because of my background as a screenwriter, I am more comfortable with the former. Ask anybody who has had the misfortune of having to edit my writing and they will tell you that my sentence structure and my punctuation are, well, “creative.”

#Writing for speaking is different than writing for reading, says @Robert_Rose via @cmicontent. #CMWorld Click To TweetHowever, if you read my raw writing out loud, it tends to sound OK.

This differentiation is why many people have challenges in writing scripts. They believe that by writing down the words for their speaking, they’ll lock themselves into a style that ends up sounding overly formal and stilted.

But moving back and forth between styles can be a strength to writing scripts that have impact. Think about movies you really like. Movies are crafted by writers who purposely use what many perceive as very stylized dialogue.

Aaron Sorkin is just such a writer. Listen to the dialogue in this clip from The Social Network. Notice how formal the words are, how carefully chosen they are, and how they sound to give the story just the right edge.

On the other side are movies that, at first, seem to have dialogue so natural that you think the actors are literally making up the words as they go. Think of a movie like Juno or any Quentin Tarantino movie.

Listen to the dialogue in this clip from Juno and to how naturalistic the dialogue sounds.

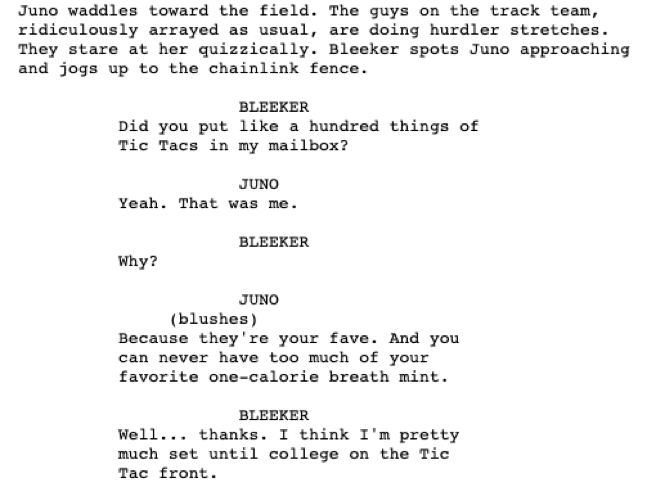

You can hear the difference, right? You might think that it’s just in the performance. But it’s not. Here’s the script from a part of this scene by screenwriter Diablo Cody.

Notice the script is written as people really speak, in fragmented sentences, and the use of “pretty much” as an adverb. When was the last time you wrote “pretty much”? However, it pretty much works in this case.

Neither the naturalistic or stylistic approach is wrong or better than the other. Each uses the style to tell a kind of story. No one speaks like Aaron Sorkin and Diablo Cody write. They write not how we talk but how we want to talk.

Good scripts deliver the story and the instructions to tell the story the writer wants told. A great script sounds like you. The style gives you the opportunity to improvise and the specific and structured turns of phrase you want to express.

So, the key is to write like you want to speak. If you’re going to write a script, then I highly encourage you to practice writing like you speak. Don’t worry about punctuation or sentence structure for now.

If you’re going to write a script, then I highly encourage you to practice writing like you speak, says @Robert_Rose via @cmicontent. #CMWorld Click To TweetMight you write verbal pauses and ums into your script? Yes, definitely. Consider this portion of the script from one of my introductions to the CMI’s Weekly Wrap podcast:

So let’s wrap it up shall we….

Our theme this week – Waaaiit… for it….. No uh… literally “wait for it”… that’s the theme.

This is… The Weekly Wrap.

Hello everybody, and welcome to episode #70 of The Weekly Wrap, our weekly play on words at play in the world of quarantine this week….

To land the joke on the theme – I wanted to make sure I said it just the way I wanted to say it. I wrote it out as dialogue as I heard it in my head. However, I also really like the phrase, “Our weekly play on words at play in the world this week,” so I’m very specific about the way each word is put there.

Yes, this means you’ll probably have two versions of your pieces. For example, you use the script for the webinar and derive another version for a blog post.

And that brings me to the second secret.

Secret 2: Use the stories within the story

In dramatic script writing, there are two basic types of monologues: active and narrative. In an active monologue you (or the character) speaks as a way of taking action or achieving a goal. It might be to change someone’s mind, convince them of something, or communicate a point of view.

A great example of this happens in A Few Good Men (another movie script written by Sorkin). In it, Col. Nathan Jessep, played by Jack Nicholson, has had enough of this courtroom nonsense:

The second type of monologue is a narrative monologue where you are telling a story within the story, often referring to something that happened. These monologues are used to make an analogy or to better explain a point you are making.

A great example of this is when shark hunter, Sam Quint, in the movie Jaws tells the story of his experience on the U.S.S. Indianapolis and the resulting shark attack. It’s beautifully placed in the story, as it brings a horrific story to life and illustrates how much danger the three heroes are in:

In your work as a content marketer, you will no doubt use both active and narrative. Mixing them up is essential to writing a great script. The key is to know the differences and how you place and balance them in your script. If you put in a narrative monologue without a purpose, the audience will immediately pick up on it. Any time you listen to a podcast or watch a video and ask, “Why is he telling me this story,” you know the narrative monologue is out of place.

Mixing up active and narrative monologues is essential to writing a great script, says @Robert_Rose via @cmicontent. #CMWorld Click To TweetAdditionally, too much of one monologue type or the other and you may lose your audience.

For example, at Content Marketing World 2019, my pal Joe Pulizzi illustrated this well. His time slot was 20 minutes. We needed to have him hit that mark. So, Joe’s keynote presentation was extremely tightly scripted. Note the length of his talk in the YouTube video. That’s right, it’s 18:02. He hit his mark beautifully.

But, more importantly, watch how Joe introduces his talk, then how he shifts gears 20 seconds in and places a narrative monologue. Two things are important here. First, the “story within the story” is relevant on its own. Second, it feeds a purpose to the larger story. For Joe it served as a personal example of his first law.

Pay close attention to how your scripted story is unfolding. Ensure that your narrative monologues feed your larger active monologues and that you have a balance of both.

That brings me to the third secret of great scripts.

Secret 3: Know it, don’t read it

You might think after all that talk about writing like we speak and focusing on structure that the advice for performing a great script is to simply read it as you wrote it.

Nope.

Once you write your script, you need to work your script until you know it. Do you have to memorize it? Well, if you’re giving it as a keynote or session, then yes. Unless you’re a celebrity, you’re probably not going to get a teleprompter at your next event. You at least need to memorize it until you feel you have it down.

If you’re doing a podcast or the voiceover for a presentation, then no, you don’t need to memorize it. But in either case, the first step to a great performance of a great script is to find your cadence, your inflections, and which words make sense to emphasize.

As part of this article, I am including the script for this video. Download it to see how similar and different it is from the written post. You can see which words I bolded for emphasis, and where I noted pauses, or capitalized words so that I would know exactly how I wanted to deliver them.

This doesn’t have to take long. When I write my weekly podcast, I spend about a half-hour working through the script – and I script just about every word of every episode. The more you know your script, the better your performance will be. This is especially true if your audience is going to see you.

If you write a script, then you can not only know the words but the way to deliver those words. Watch the absolute master of this, comedian Jerry Seinfeld. He has talked many times to how his performances are scripted word for word, down to the emphasis of the words. Watch this video and pay attention to just how each line is delivered in a particular (and very Jerry) way:

Steal like an artist

To this day, I watch comedians, movies, and even politicians for the effective ways they use scripts. I have found the best way to get better at scripts is to, well, copy great scripts. This is harder than it sounds because it’s not about looking at transcripts of great performances. Capturing the performance in written word isn’t the same as seeing how the performance was translated from the written word.

For movies, you can get access to a surprising number of scripts. Do a little Google-fu for what you’re looking for and you’ll see that many modern and classic movie scripts are online, waiting for you to read.

For speeches, especially for politicians, you can usually find their prepared remarks fairly easily as well. Without naming names, it’s worth looking at the good ones and the really bad ones to feel where the challenge was – with the script or the performance.

For others such as voiceovers, videos, etc. pay attention to the performance. It’s easy to tell when someone is reading something that isn’t written as a script.

Watch this video and you can see where this guest turns and reads something on the teleprompter that clearly was not written as a script. See how much more natural she gets when she actually goes off “script” or responds to a question:

In the end, writing great scripts is simply about capturing exactly the way you want to communicate. Scripts are great tools. The best tell the story clearly but allow for great performances to elevate it to another level. As classic Hollywood film director Howard Hawks said, “You can’t fix a bad script after you start shooting. The problems on the page only get bigger as they move to the big screen.”

Take the time and write a great script, so you can focus on your performance.

And remember … it’s your story. Tell it well.

Now, watch my video of this post to compare and contrast:

HANDPICKED RELATED CONTENT:

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute